“Though it is now underground, Brewery Creek is still alive . . . you can hear it!”

As Vancouver City Archivist Major James S. Matthews insisted in the mid twentieth century, the spirit of Brewery Creek is still alive and well today.

Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood is currently home to some of the city’s most successful craft breweries. Those in search of a pint can easily walk from Red Truck Beer Co. to Brassneck Brewery and Main St Brewing, then across to 33 Acres Brewing, Electric Bicycle Brewing, Faculty Brewing, and R&B Brewing. It’s one of the best walkable brewery crawl routes around.

However, many craft beer fans may not be aware that under the pavement still runs Brewery Creek, whose waters initially supplied or ran alongside the earliest breweries in the city — Vancouver Brewery (and its successors), Mainland Brewery, San Francisco Brewery, Red Star, Lansdowne, Stadler, and perhaps more. As salmon-filled fresh water coursed down from Tea Swamp, eventually emptying into the original False Creek (where Red Truck is now), it was collected to brew beer and to power breweries’ grain mills.

Charles Doering and Vancouver Brewery

The first brewery in Vancouver actually wasn’t near Brewery Creek, but it inspired one that was. City Brewery on wealthy Seaton Street (currently the area of Hastings west of Burrard) was a small steam-beer brewery opened by J. Rekab in 1887, just one year after the City of Vancouver’s incorporation.

We know almost nothing about Rekab, but we do know that City Brewery caught the eye of Charles Doering, a German immigrant who had recently moved to Vancouver from Victoria, where he had been running a saloon and working in the Phoenix Brewery. In Victoria, Doering was proud to sell locally brewed Empire beer for 5 cents a glass at his King’s Head Beer Hall – and this was at a time when many publicans were still relying on beer imported from the US and Europe, despite Victoria’s burgeoning brewing industry. Doering knew that his newest venture in Vancouver, the Stag & Pheasant Hotel on Water Street, would need a beer supply, and he wanted to expand beyond imports. However, there was only the one local brewery in Vancouver: the City Brewery. Doering saw a gap in the market and an exciting business opportunity.

In 1888, shortly after marrying Sarah Jane Helgesen of Victoria and celebrating with a honeymoon in San Francisco, Charles Doering purchased a property on Scotia and 7th and transformed it into Vancouver Brewery. He dammed Brewery Creek and used it to power the brewery’s mill.

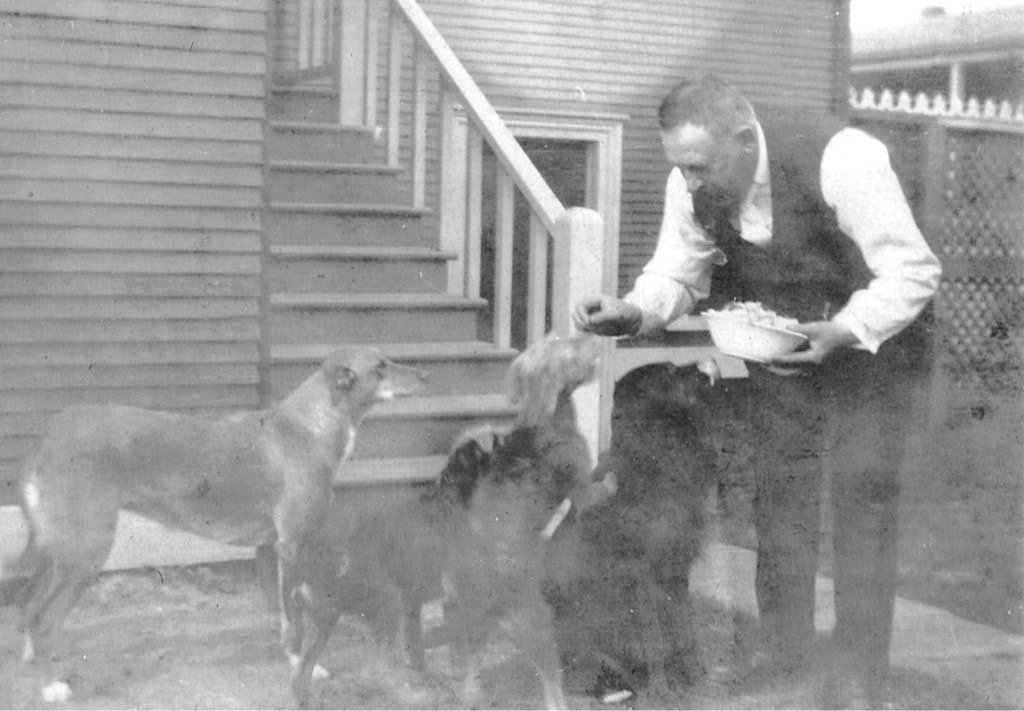

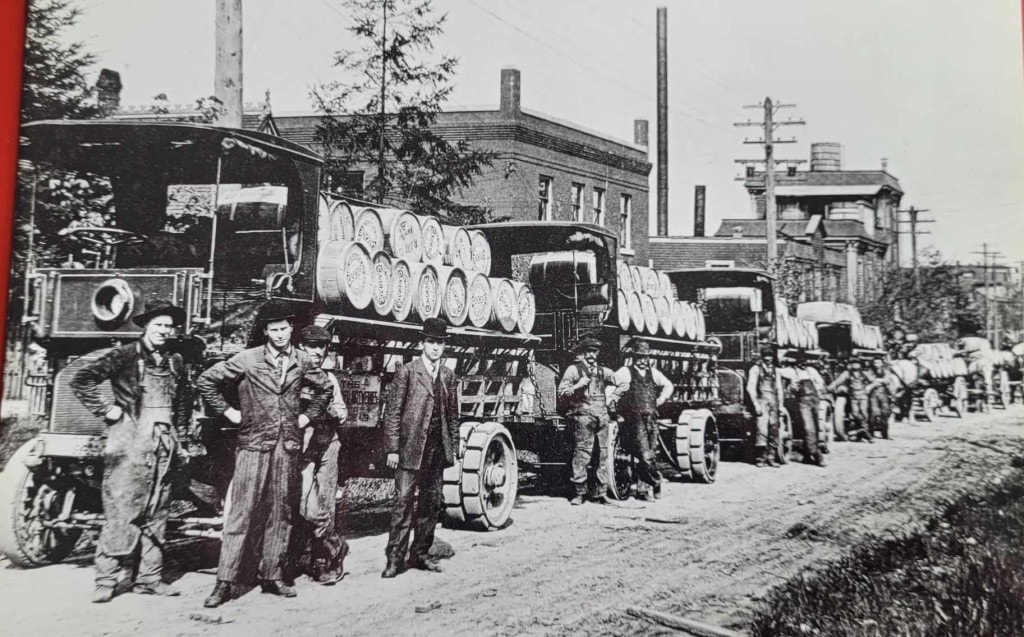

Eventually, most of the block became brewery property, including Doering’s family home, the stables, and the brewery warehouse. Doering’s horses (which were used to pull the brewery wagons to deliver kegs) and beloved dogs populated the lot, along with brewery workers and carriages. It was an exciting and busy time in Mount Pleasant.

This first Vancouver Brewery looked nothing like the current structure that sits on the same lot — the building that now houses Main Street Brewing. That facility, a beautiful yellow and white heritage building today, was built around 1920 and became the garage for Vancouver Breweries (the later version of Vancouver Brewery) in the ‘20s and ‘30s. The original Vancouver Brewery was constructed in 1888 and opened with a 1500-gallon-per-day brewing capacity. This three-storey building was made of wood, brick, and fieldstone.

Changes, Competition, and Consolidations

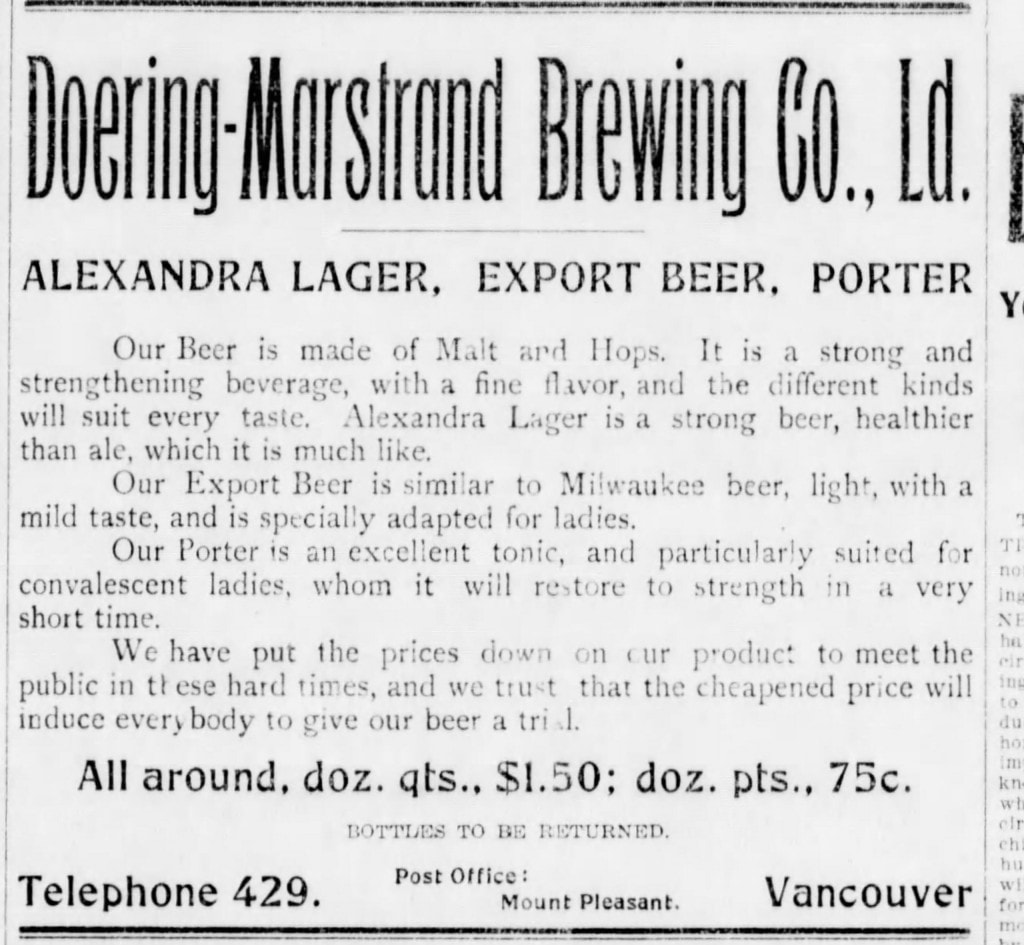

Doering’s efforts met with success, so much so that by 1892 he was able to hire a brewmaster from Denmark — Otto Marstrand — to join him as a partner. The brewery was renamed Doering & Marstrand Brewery (or D&M Brewery) that year, and a celebration was hosted at the brewery for its inaugural lager. Lager was the drink of choice in Vancouver — a contrast to Victoria, where English-style ales were still in fashion.

Doering’s biggest brewing competitor was there at the D&M party: John Williams, an Englishman who bought out Rekab’s City Brewery and renamed it Red Cross Brewery. One ad in the Daily News Advertiser explained the Red Cross brand identity:

“The red cross stands on the battlefield for help; in Vancouver it stands for pure beer [. . .] unadulterated with any of the foreign abominations that are injurious to health.”

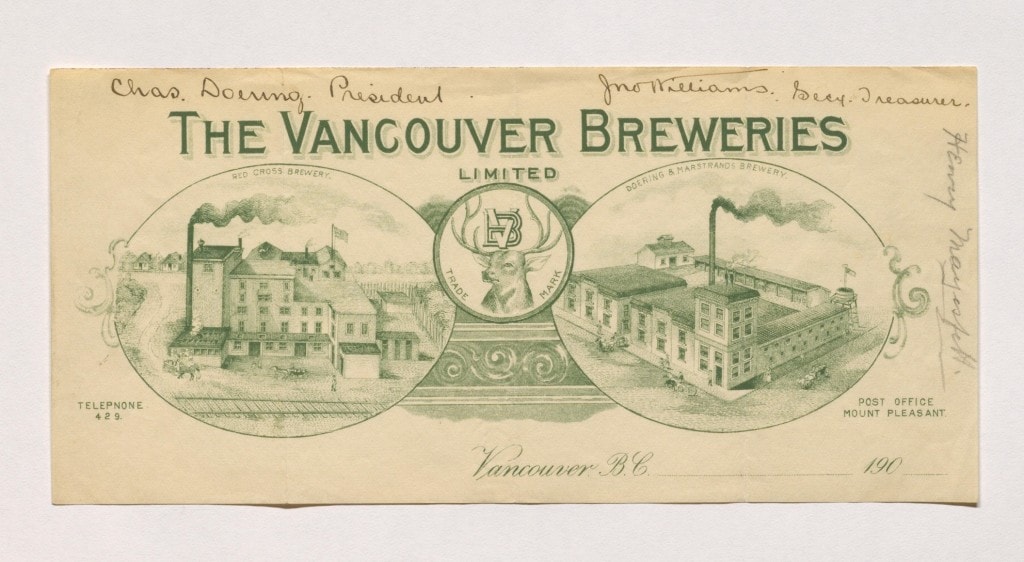

Like D&M, Red Cross began advertising their authentic German lager (made by their German brewmaster, Henry Traeger) in the early 1890s. However, it soon became clear that D&M and Red Cross were more friends than enemies. They attempted price-fixing in 1893, and by the mid-1890s they had a monopoly in the Vancouver beer market. By 1902, they announced their amalgamation. Red Cross shut down its facility on Seaton Street and Henry Traeger joined the brewing team at the newly-named Vancouver Breweries on Scotia and 7th. John Williams was the secretary and Charles Doering was president. “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em!” was the name of the brewing competition game in early Vancouver.

A popular city-wide contest to name Vancouver Breweries’ flagship beer soon got the word out about the amalgamation. For a chance at a $50 prize, thousands of citizens sent in their name suggestions, from “Kitsalano” to “Acme.” The winner, however, was Cascade. Cascade beer would end up being one of the best-selling beers for decades. It was advertised in local papers as “beer that is as pure and healthful as the rippling waters of a mountain brook … contain[ing] only the purest and most healthful of ingredients … [It] is a drink fit for the most delicate lady.”

Charles Doering’s life became more busy and more complicated while his brewing career boomed. In 1893, he and his wife Sarah, who already had a four-year-old daughter, lost their ten-day-old baby. In 1906, Sarah died due to complications resulting from a tuberculosis treatment in Germany. Their daughter Beatrice, who was travelling with them at the time, wrote home to let family know the sad news, expressing both sorrow and relief that her mother’s long suffering was over.

Business boomed in the years after Sarah’s death, but Doering began to spend increasingly more time at his ranch properties, especially Hat Creek Ranch near Ashcroft. He had plans to transform the Vancouver brewing scene by creating a holding company that would unite BC’s breweries. With the help of beer baron Henry Reifel of Nanaimo, whose San Francisco Brewery on the shores of Brewery Creek was short-lived, Doering did just that. Vancouver Breweries joined Reifel’s new Vancouver brewery, Canadian Brewing and Malting, along with his Union Brewery of Nanaimo and Pilsener Brewing of Cumberland under the umbrella of B.C. Breweries Ltd. Doering’s old brewing facilities at Scotia and 7th were turned into office space and all brewing was moved to Reifel’s impressive new facility near Yew and 11th (which would become the Carling brewery decades later). Classic Vancouver beers like Heidelberg, BC Export, and Cascade were made there for years.

Doering and Reifel had a falling out shortly after the founding of B.C. Breweries and the company fell into financial trouble. After some legal wrestling, an agreement was reached and Reifel was left with a resurrected version of B.C. Breweries while Doering turned to other business interests and exited the brewing scene. Over the decades, through a series of mergers and acquisitions, BC Breweries would eventually be acquired by Carling O’Keefe, which in turn was acquired by Molson-Coors. Doering, once he left brewing, found health and happiness with a new marriage and grandchildren. He spent much of his time hunting and fishing at Hat Creek Ranch, accompanied by friends — this included Red Cross and Vancouver Breweries brewmaster Henry Traeger and his family, with whom Doering had become very close. The horses who had pulled the brewery’s wagons for years received restful retirements on the ranchlands. According to Doering’s great-great-grandson Dennis Mutter, he had a soft spot in his heart for animals.

Mainland Brewing

Vancouver Brewery (a.k.a D&M Brewery, a.k.a. Vancouver Breweries) wasn’t the only start-up near Brewery Creek. There was also Mainland Brewing, which opened just a couple of blocks south of where 33 Acres is now. In 1888, German immigrant Robert Reisterer moved from New Westminster, where his City Brewery had burned down, and opened a new brewery “quite in the bush,” according to papers. That side of Main Street was, in the 1880s and 1890s, mostly a cluster of trees, bushes, and creeks. Reisterer made a special funding application to City Council to build a road off Quebec Street so people could actually get to his brewery. However, despite all that effort he didn’t seem to have much interest in staying in Vancouver. The brewery had only a third of the brewing capacity of Doering’s Vancouver Brewery and there are almost no advertisements for it in contemporary newspapers. Reisterer wanted out of Vancouver: he repeatedly spoke of his dream to open a brewery in the Kootenays. The brewery was up for sale in the early 1890s and Reisterer and his wife Clara moved to Kaslo shortly thereafter, following a raucous goodbye party that included plenty of Red Cross beer and a performance of the local German men’s choir. An attempt to open a brewery in Kaslo wasn’t successful, but he had more luck in Nelson, where he established the first Nelson Brewing Company. (For more on that story check out this blog.)

The Little Guys

There were a few more breweries in early Vancouver that started up and sank without much of a trace. I already mentioned San Francisco Brewing, which was opened by Henry Reifel and his brother the same year Doering started his Vancouver Brewery. They closed within a year and auctioned off their equipment. Red Star Brewery opened in the same location immediately afterwards but closed a year or two later. In a similar pattern, Lion Brewing and Stadler Brewing both occupied the same property on 2nd (where Red Truck is now) in quick succession, neither lasting longer than two years. One possible reason could be location: the San Francisco site was close to the tannery and the Lion Brewery at the mouth of Brewery Creek was near the slaughterhouses (see the map below). Brewing near these industries was probably not ideal!

The thriving of Vancouver’s Brewery Creek neighbourhood so quickly after the city’s incorporation showed not only the ingenuity of these early brewers and business people, but the eagerness of Vancouver citizens for locally-produced beer. These early breweries also helped to rehabilitate the alcohol industry, which had been tainted by the increasingly debauched nature of saloons at the time. Breweries were making a product marketed as family-friendly (“families supplied!” often appeared in ads) and suitable for not just working men, but for women, “invalids”, and children. Non- or low-alcohol beers, like Vancouver Brewery’s Vancouver Ale, were widely advertised, and women increasingly featured in marketing materials. While the pattern of brewery consolidations, beginning with D&M and Red Cross, and then BC Breweries, at first appeared to be a mark of economic health for the industry, we can see in hindsight that it actually spelled the death of Vancouver’s independent brewing — at least for a while. Fortunately, independent brewing has now been revived in the city and Brewery Creek is quenching the thirst of Vancouver’s beer fans once again.

Learn more about Vancouver brewing history by reading this blog by the same author.

Plan your visit with the Brewery Creek Vancouver Ale Trail.

And be sure to pick up a copy of Noëlle Phillips’ new book about Vancouver’s beer history coming out this fall!